A couple of weeks ago I stumbled into some reloading supplies at an estate sale. I bought most of it as no one else would even have an idea of what it was. I was excited to see the gentleman had the same interest as I do, this also kind of bummed me out because I never knew the man and I’m sure we could have been friends. I figure it’s only right to do justice to some of his components and enjoy them as I’m sure he did.

One of the things we will discuss today is a good quantity of cast bullets. They have no information about them but as you can see, they have a wide meplat with a reasonable cutting edge. They are sized .431 weigh 300gn on average, and as a bonus they also have gas checks.

So, we have a somewhat heavy for caliber hard cast bullet that we can put some velocity behind. Sounds like a great heavy 44mag load in the making.

With a little detective work and research, we have a solid idea of who made these bullets and how to load them.

What’s a gas check anyway?

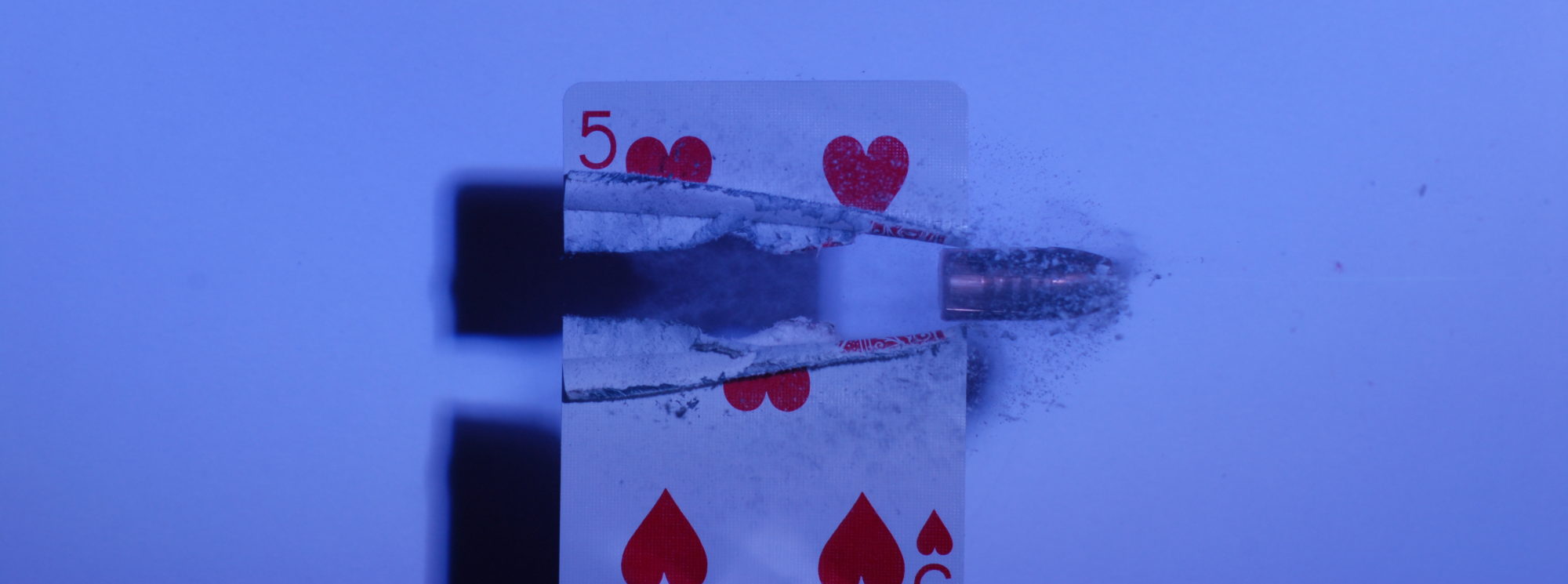

A gas check is a small metal cup, usually made of copper or aluminum, that is crimped onto the base of a cast lead bullet. Its main purpose is to protect the bullet’s base from the hot gases generated when the gun is fired. A bullet that doesn’t perfectly fit the bore will not fully seal to the bore and allow hot gas to escape by. When this happens, it cuts a groove in the base of the bullet, this deposits that molten led in the rifling and damages the bullet leading to accuracy issues.

Gas checks improve bullet performance by creating a better seal in the bore, which enhances velocity and consistency. They are typically used on bullets that are designed to be shot at higher velocities where plain base lead bullets would otherwise struggle to maintain their integrity. Not all cast bullets require gas checks, but when used appropriately, they allow shooters to push their cast loads faster and more accurately.

If you shoot cast bullets an extremely valuable resource is the Lyman Cast Bullet Handbook 4th edition. It is available from Amazon and a few other sources. The information contained in this book is a wealth of knowledge on the topic. It makes for interesting reading and is a great reference.

After a little digging and weighing we have determined these bullets are 300gn and were made by the Cast Performance Bullet Company. They are sadly no longer offering bullets to the public. I think they were bought or otherwise absorbed by Grizzly Cartridge. This is a bummer as they made a quality product and supported the reloading community.

So how do you load a projectile that you don’t exactly know the particulars of?

As I’ve said before you need to research and cross references. Finding a similar projectile and load data is the best way to get started. 300gn 44mag load data is readily available, most of it is for jacketed bullets but it does provide some rudimentary information. Honestly the Lyman Bullet Handbook is a cheat code for cast bullets and load data.

The primary difference between cast and jacketed bullet load data lies in the bullet construction and how it affects pressure and velocity. Cast bullets are made from lead or lead alloys and are typically softer than their jacketed counterparts. Because of this, they generate less friction in the barrel and require less powder to achieve safe and accurate performance. Using jacketed bullet load data for cast bullets can result in underpowered loads, while using cast bullet data for jacketed bullets can be dangerous, as jacketed bullets need more pressure to properly engage the rifling and travel safely down the barrel.

Jacketed bullets, on the other hand, have a harder metal coating (usually copper) that allows them to withstand higher velocities and pressures. Their load data is developed with this in mind, often calling for more powder and higher pressures than cast bullet data. Reloading manuals usually list separate data for cast and jacketed bullets even when the bullet weights are the same, because substituting one for the other without adjusting the load can lead to poor accuracy, barrel leading, or even firearm damage.

So, we have a good idea of what bullet we’re working with, and we’ve identified a few comparable load data sources to use as references. This gives us a solid foundation to begin developing a safe and effective load. Now it’s time to apply the tried-and-true principle of starting low and working up slowly, always watching for signs of excessive pressure or inconsistencies in performance. This cautious approach not only protects your firearm and yourself but also allows you to observe how small changes in powder charge can affect accuracy, velocity, and overall behavior of the round. Patience here pays off; rushing the process can lead to subpar results or unsafe conditions.

The advantage we have with this particular cast bullet is the addition of a gas check, which allows us to push the velocity higher without worrying about lead fouling in the bore. This opens up more flexibility in the load range, especially for a heavy 300-grain bullet in .44 Magnum, which can be a powerful and effective option for hunting or long-range target shooting. With some fine-tuning of the powder charge, seating depth, and crimp, we can dial in a load that delivers tight groups and consistent performance. With the right combination, this setup has the potential to be both hard-hitting and highly accurate.

Never be afraid to pick up reloading components, even if you’re not entirely sure what they are or how you’ll use them right away. Of course, gunpowder requires extra caution and proper identification, but beyond that, going on an investigative journey to learn about unfamiliar bullets, primers, or casings can be both fun and highly rewarding. Digging into old manuals, online forums, or chatting with experienced reloaders often turns into a valuable learning experience.

You might even discover new load combinations or unexpected performance from gear you already have. For example, I know Jay has been toying with the idea of repurposing his .338 Lapua Magnum into a close-quarters room-clearing monster; not because it’s practical, but just to see what’s possible with creative use of nonstandard components.

This kind of experimentation is one of the most enjoyable parts of reloading. It’s not just about duplicating factory ammo, it’s about exploring, learning, and getting the most out of your equipment. Breathing new life into a rifle or revolver that’s been sitting in the safe can reinvigorate your interest in the hobby without requiring a big investment. Plus, it challenges your understanding of ballistics, pressure curves, and firearm behavior in a way that keeps you engaged and constantly improving. Sometimes, the best range days start with the most unlikely combinations, and that’s where the real fun begins.

Marc